Optimising Recovery

by Doug Stewart

With Black Friday fast approaching there are likely to be lots of adverts and discounts on a huge number of ‘recovery’ devices. But are they actually worth investing in, even with a Black Friday discount?

Figure 1: The Fundamentals of Recovery – the Cake, and some of the ‘Icing on Top of the Cake’ strategies for Recovery. Source: Driller and Leabeater, 2023

A narrative review published at the start of the month provides a good summary of the research to date on different approaches and devices for recovery. Importantly, the authors initially also discuss the value of sleep, nutrition and a periodised training plan that has recovery incorporated into it.

These elements have the most evidence supporting their use and effectiveness. They should be key focus areas of athletes, as this is where significant improvements can often be made.

As the authors explain:

Athletes’ perceptions of recovery methods often do not align with current scientific evidence (Crowther et al., 2017), and as such, athletes may overlook some of the more well-established methods of recovery in favour of new or novel recovery technologies. While research evidence is weak or sparse on many of these newer technologies like massage guns, occlusion cuffs, and recovery boots/sleeves, there is a greater level of empirical support for the fundamental recovery strategies of sleep, nutrition, and periodisation and their role in athletic recovery. These fundamentals (“the cake” - Figure 1) have a much greater overall contribution to athletic recovery and performance than any potential marginal improvements from added devices/tools (“the icing”) and must therefore be monitored and optimised before considering the implementation of further strategies or devices.

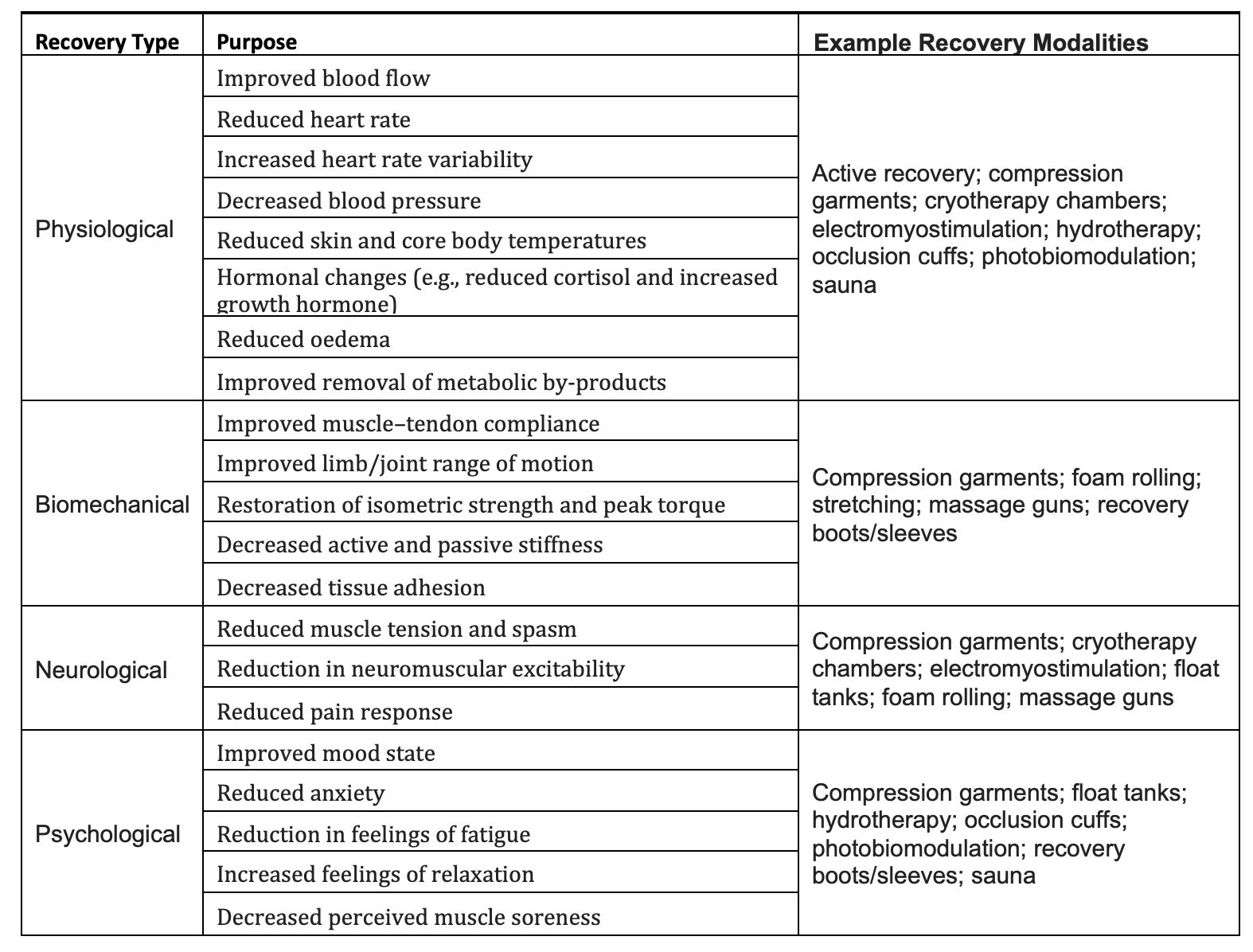

When it comes to recovery, there are various elements to consider – Physiological, Biomechanical, Neurological and Psychological. The authors provide details on the purpose of each of these and examples of recovery devices that ‘may’ help improve recovery.

The paper discusses the recovery devices/modalities that have had the most research conducted on them. This does not mean that the research suggests the devices/modalities are beneficial, just that they are heavily researched. Once again, it is worth highlighting as well that these devices are secondary to the fundamentals of recovery in the ‘cake’.

The key areas or research were on the following devices/modalities:

Foam Rolling

Some evidence shows that foam rolling improves range of motion following working out – with around 90 to 120 seconds per muscle group deemed optimal. It also may help reduce delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMs). However, there is limited evidence that increased range of motion or decreased DOMs actually improves performance.

Compression Clothing

The evidence generally tends to show a positive impact on recovery, especially for strength training, and may help endurance performance the following day.

Electrical Muscle Stimulation

Findings are generally inconsistent with EMS, and, they can also cause pain and discomfort when using them. Part of this inconsistency may in part be due to the devices and protocols used in the research.

Cryotherapy Chambers

A 2014 review suggested no recovery benefit, but a more recent study suggested benefits after damaging exercise. There were also potentially lower markers of muscle damage.

Cold Water Immersion and Contrast Water Therapy

The reviews generally show some benefits of these approaches for certain sports. In strength training, research has revealed the chronic use of cold water immersion blunted training adaptations over time, but this has not been proven in aerobic exercise (maybe due to the potential small recovery benefits allowing endurance athletes to increase training load).

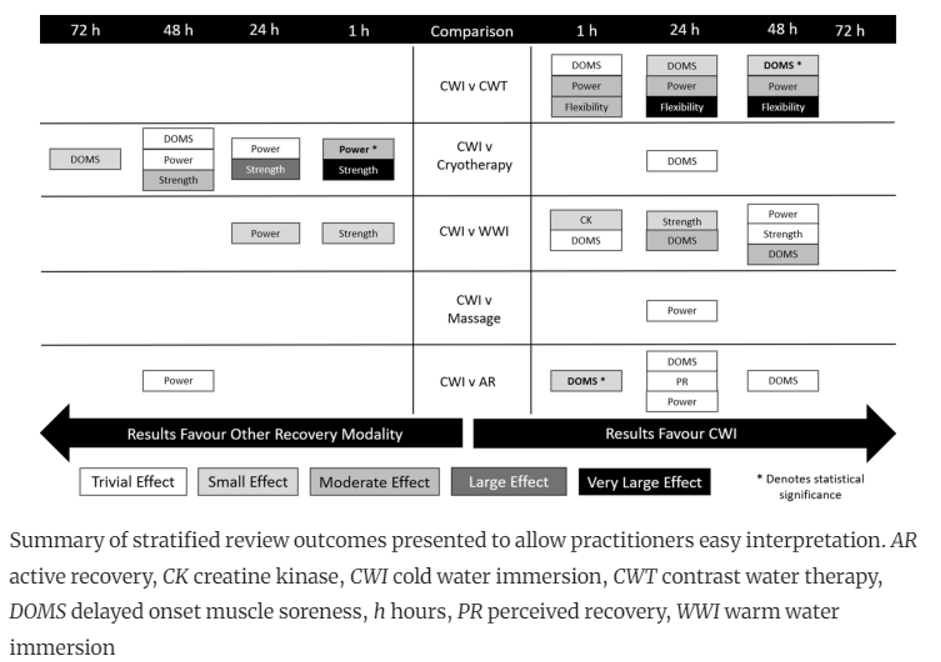

A recent meta-analysis provided this summary comparing cold water immersion versus other recovery strategies.

Source: Moore et al., 2022

Overall, it appears that generally there is a small effect and often not statistically significant.

Active Recovery

A review of 17 studies on active recovery (including activities like yoga) showed that there was a reduction in perception of soreness following hard training, but that it led to mixed results on indicators of performance. Plus, active recovery does increase total energy expenditure, which should be considered.

Stretching

Recent reviews have shown stretching not to be more beneficial that passive recovery/rest on DOMs or recovery of strength. It appears that most studies on stretching have poor external validity and so may not be reflective the real world.

Other recovery modalities with less research on them include:

Sauna

There do not appear to be any systematic reviews or meta-analysis on sauna use following training. It is known that saunas do add an additional stress and so should be used with caution if being implemented for recovery purposes.

Recovery Boots/Sleeves

Like saunas, there appear to be no systematic reviews or meta-analysis of them, but the research that has been conducted shows similar results as with compression clothing – which is often considerably cheaper.

Massage Guns

The limited research on massage guns is mixed. There may be some benefits in increasing range of motion and reducing stiffness, but two case studies have highlighted serious injuries from their use. Another study showed increases in lower leg pain following their use for 5 minutes following hard training.

Overall, it appears that most devices/modalities provide mixed results to small impacts. It is, however, worth considering the impact of the placebo effect on the results as some measures discussed are subjective and it would be difficult to provide a placebo for a lot of these devices. Therefore, the participants were aware of what they were doing and what the role of the devices/modalities was meant to be when they were using them, which could influence their results.

Additionally, the research was not solely on endurance sports, so some of the small benefits mentioned have been researched in other sports, with the benefits not necessarily transferring to endurance sports.

So, when looking for Black Friday deals, maybe devices that improve sleep hygiene quality (Biggins et al., 2019) or enhance your nutrition may be the first place to find recovery/performance gains.

References:

Biggins, M., Purtill, H., Fowler, P., Bender, A., Sullivan, K. O., Samuels, C., & Cahalan, R. (2019). Sleep in elite multi-sport athletes: Implications for athlete health and wellbeing. Physical Therapy in Sport, 39, 136-142.

Crowther, F., Sealey, R., Crowe, M., Edwards, A., & Halson, S. (2017). Team sport athletes’ perceptions and use of recovery strategies: a mixed-methods survey study. BMC Sports science, medicine and rehabilitation, 9(1), 1-10.

Driller, M., & Leabeater, A. (2023). Fundamentals or Icing on Top of the Cake? A Narrative Review of Recovery Strategies and Devices for Athletes. Sports, 11(11), 213.

Moore, E., Fuller, J. T., Bellenger, C. R., Saunders, S., Halson, S. L., Broatch, J. R., & Buckley, J. D. (2023). Effects of Cold-Water Immersion Compared with Other Recovery Modalities on Athletic Performance Following Acute Strenuous Exercise in Physically Active Participants: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Meta-Regression. Sports Medicine, 53(3), 687-705.